14th October 1914

The only good news anyone had experienced for a couple of days crawled back through the battlefield during the night. Lieutenant Colonel Bols had dragged himself back to the Dorsets at Pont Fixe. His escape is a story straight out of the pages of Boys’ Own. The Germans had let a great prize slip through their hands.

Bols lay injured on the ground as the Germans surged over their position. Any immobile British wounded were taken prisoner. The German stretcher bearers soon arrived to pick among the wounded and Bols was told to wait for an ambulance. So he waited. And waited. Dusk came and so he began what much have been an agonising crawl back to the British line. Agonising because of his wounds, but also mentally as he crawled through the fallen heaps of his once proud Battalion.

Sadly there’s no first person account of his adventure, nor is there any more information about this other than the story above. We’ll catch up with Bols in the future but for now the Dorsets were in the capable hands of Major Cyril Saunders.

One more officer crawled back to the lines. Captain Francis Hans Bunbury Rathborne had been assisting the 18-pounders by the spoil heap when he was severely wounded. I’m happy to say that he survived the war and lived a long life, dying in 1976 aged 87.

First thing in the morning the sad remnants of the three Companies, B, C and D were merged into, what the war diary calls, a Composite Company. They were led by Captain Henry Beveridge who must have been an officer from the previous reinforcements as he’s not on the original list sent out from Belfast. They were sent away along the canal to the west out of the action.

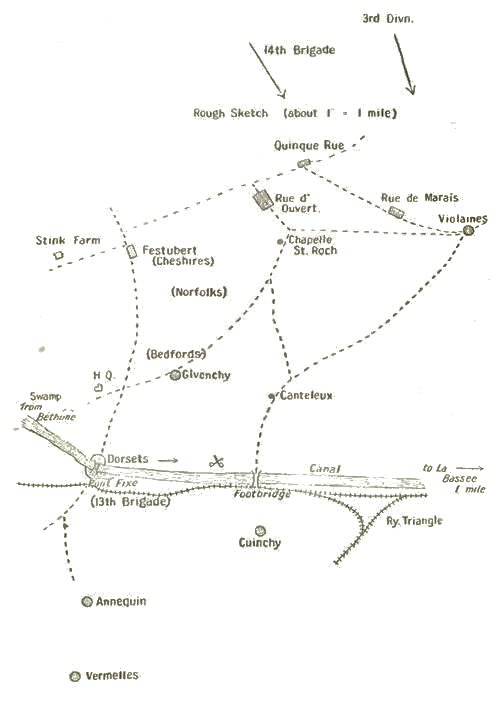

Meanwhile the battle continued for a third day. The British continued to try to push through to La Bassée. The 15th Brigade was trying to move on, so that the 3rd Division to their north could swing round into the gap. Again the 13th Brigade was held up and the Dorsets couldn’t get forward without experiencing the dreadful enfilade fire from the Germans hidden behind the raised bank on the south side of the canal.

Gleichen’s hand drawn map shows the situation in more detail. Some of the positions aren’t the same as they stand today; Cuinchy is now more to the left directly south from the Pont Fixe.

Frank and the rest of A Company hunkered down in the factory at Pont Fixe and soon came under withering shellfire. A message came fro Gleichen. “Pont Fixe must not be given up. I know I can rely on you to stick to it with the help of the Devons”. Two more companies from the Devons arrived to support the skeleton 1st Battalion Dorsets.

At 2pm the French attacked at Vermelles to the south. At 5pm A Company got the orders they must have been dreading. They were to support an attack by the Devons along the same line north of the canal they had tried for the last two days. But they weren’t to move until the 13th Brigade advanced on the south bank of the canal.

Luckily for A Company, the Germans attacked the 13th Brigade and pushed them back. By 8:30pm the Germans were now attacking the north side of the canal. A Company and the Devons held on and only three men were wounded, although three deaths are listed on CWGC, presumably they died from wounds sustained over the last couple of days.

Frank had survived another day.